Coulomb Keeper

I need to tell you all about 3D printing flying R/C planes, and I will. It’s really cool! But this blog is about a different type of 3D printed airplane. It’s called the Coulomb Keeper.

While at the Sustainable Aviation Symposium, I introduced myself to Phil from How Flies The Albatross. He had given a fascinating talk about his ideas for electric flight and briefly presented two concept planes. The Coulomb Keeper is the smaller, more general aviation model. The larger, jet like, model is called the Faraday First and perhaps I’ll blog about that one later.

So I asked Phil if he’d be willing to share he aircraft designs with me so that I could print them and see how they fly. He agreed! In fact he asked if I could print him a smaller “draft” model and take pictures for his next presentation. What he sent me were Blender files. Blender is a 3D modeling tool that is used for amination, games, and a variety of things, but I had never used it before. Fortunately it’s open source, and free! Unfortunately, a yak must be shaved to get from Blender .BLEND files to 3D printable .GCODE files. Allow me to describe the yak.

.BLEND -> .OBJ

My tool of choice for 3D modeling is Fusion 360, which is aimed more at engineering modeling. I downloaded Blender, installed it, opened the .BLEND files, and exported them to .OBJ files. Now, you’ll see below that I’ll eventually need .STL files and Blender can export these. But the model needs modification before we can print it. Why? Mostly because it’s too big. My printer (a Craftunique CraftBot 2) has a print volume of about 8 inches cubed. Whereas the printed result has a wingspan of over 2.5 feet. So I need to work with the model in Fusion 360.

.OBJ -> T-Splines

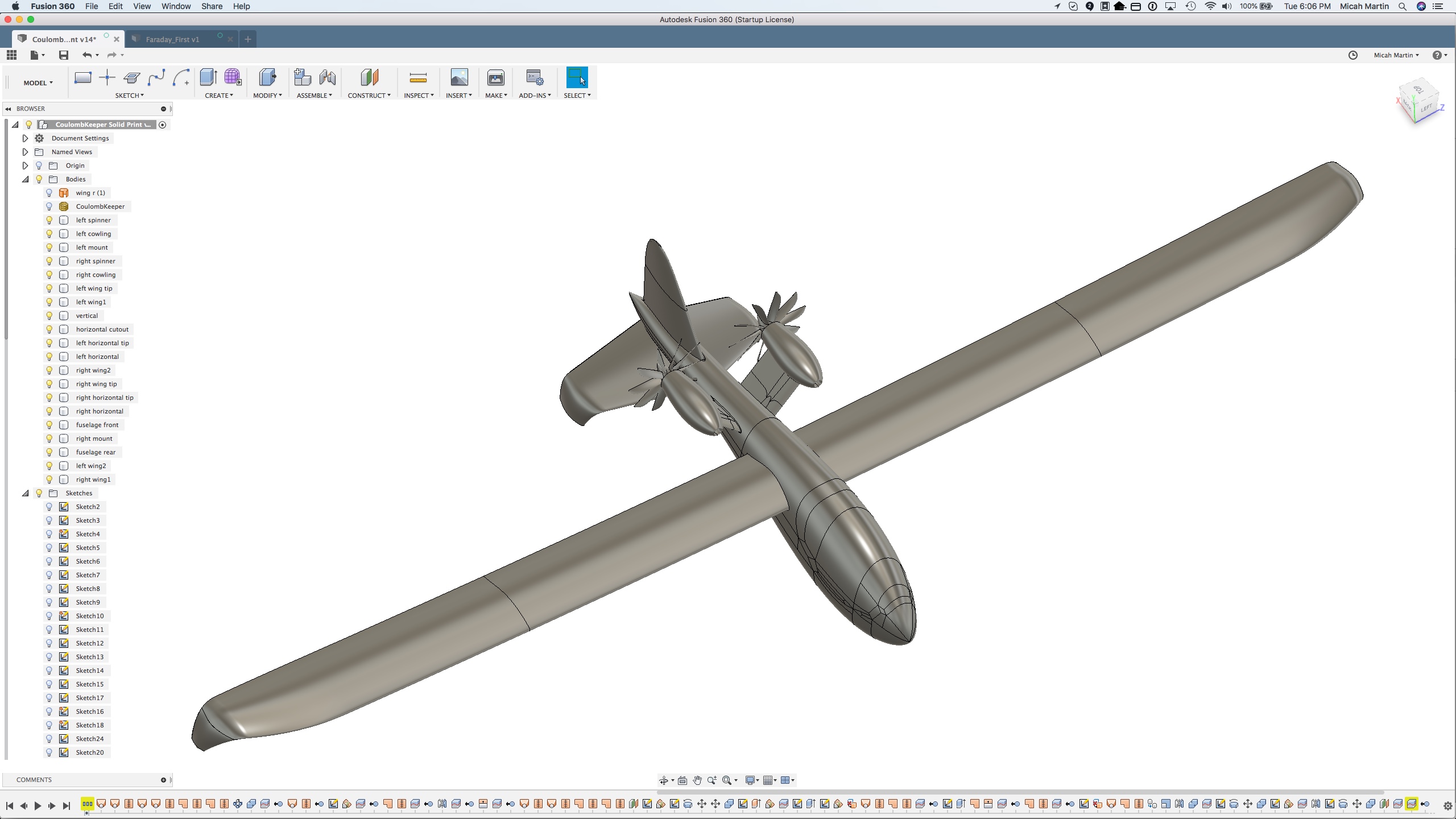

The Coulomb Keeper .OBJ file imports easily into Fusion 360 as “Mesh”. Meshes consist of a lot quadrilaterals or triangles that model the outer skins of an object. However, they are inconvenient for typical manipulations that we’d like to perform, and they are not solid, which is we want. Fusion 360 has a feature to “Convert Quad-Mesh to T-spline”. This breaks up the conglomerate Mesh into all the composing pieces (propeller blades, wings, wheels, etc.) in T-Spline format, about 30 of them. What’s a T-Spline? Well, a T-Spline is like a complicated Mesh, and a patented specialty of Fusion 360.

T-Splines -> Surface Bodies

T-Splines, although powerful, are not what we want. We want Solid Bodies. Fusion 360 can “Convert T-Spline to BRep” which get’s us close. A BRep, Bourdary Representation, or Surface Body, is nice smooth model of the skin of the object, which gets us close to Solids. But, only a fraction of the T-Splines successfully convert into BReps. Fusion 360 just can’t deal with the geometry of some of the parts. With some clever tweaking it’s usually possible to successfully convert to Surface Bodies without compromising too much on the exact shape of the model.

Surface Bodies -> Solid Bodies

To convert a Surface Body to a Solid Body, you simply patch up all the holes and they magically convert. Of course it’s never that easy. Some surfaces have unpluggable holes for whatever reason. Fusion 360 just chokes on some geometries. Progress requires that some parts get re-modeled from scratch. At the end, we have Solid Bodies.

Hurray! Now we can work with the model. Mostly that means combining all the Solid Bodies and cutting them into pieces that will print in the 3D printer; flat bottom surfaces, no overhangs, <45° horizontal angles, and all dimensions less than 200mm. See the Solid Body model below.

Solid Body -> .STL

.STL files (Standard Triangle Language) are the universal format for 3D printable models. Fusion 360 embraces 3D printing and makes it easy to export models as .STL files. I tend to export each of the Solid Bodies individually. Soon I will have to learn how use Fusion 360’s STL features to combines parts in one file and better prepare them for printing.

.STL -> .GCODE

CNC (Computer Numerical Control) machines often consume GCode files which contain detailed commands telling the machines exactly what to do. That’s true for 3D printers. Generating GCode from STL is non-trivial and requires the use of a Slicer. Slicer software allows you to control many aspects of a print job; layer thickness, speed, infill, supporting structures, etc. There are many open source, free Slicers out there, but I use Simplify3D because it was recommended and I find it simple and effective. There’a bit of art involved in good Slicing, but these parts were not particularly challenging.

.GCODE -> Printed Model

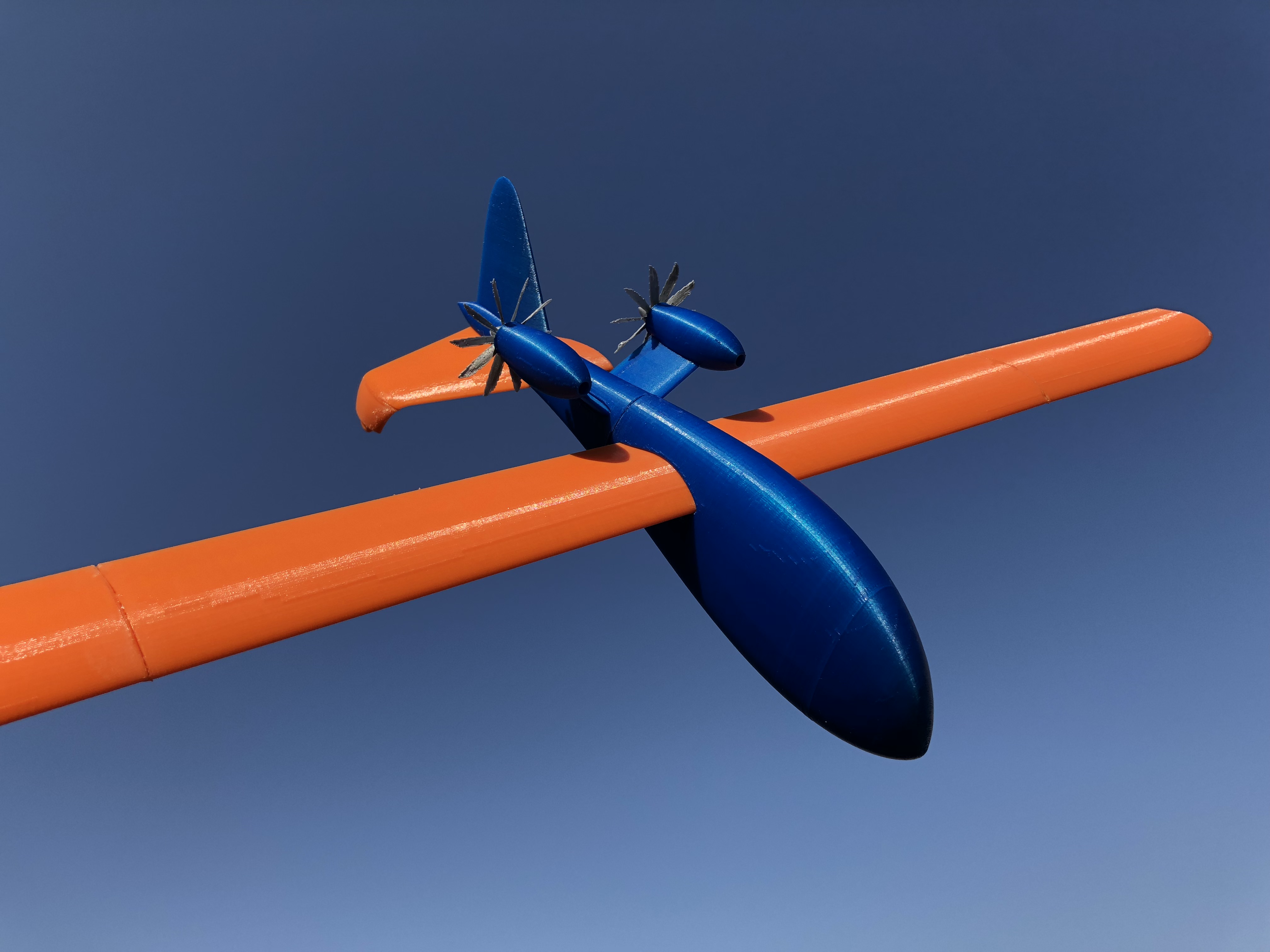

Fast forward through roughly 18 hours of printing and a little bit of time trimming, sanding, and gluing the parts together. We now have a Coulomb Keeper, in the flesh,… or plastic.